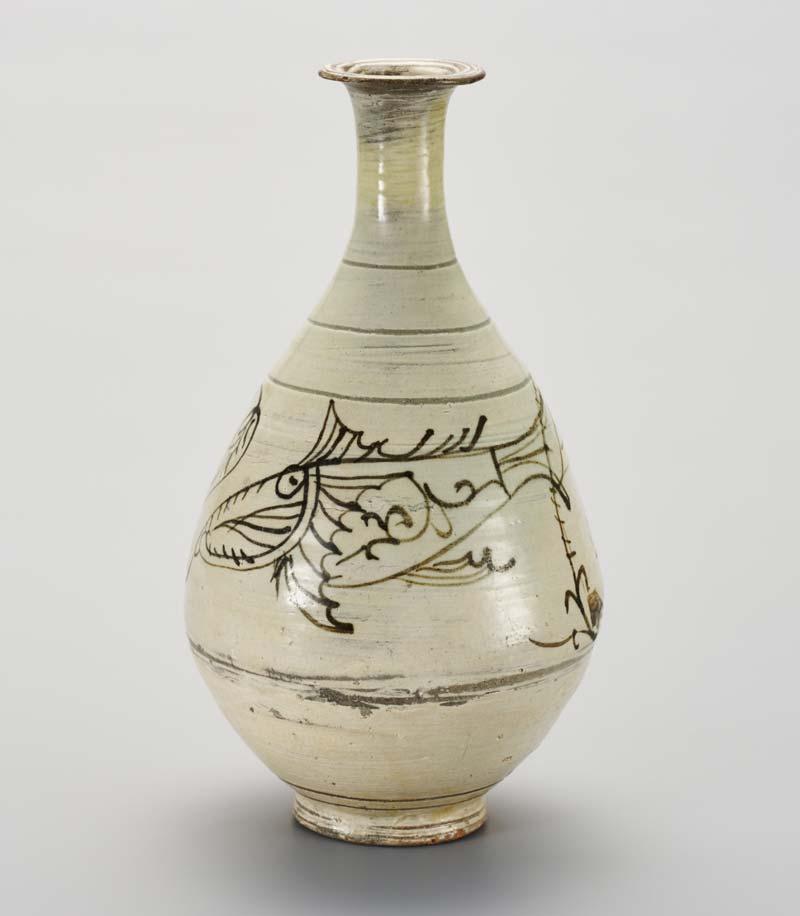

At Denver Art Museum (DAM) a compelling ceramics exhibition showcases a longstanding tradition of earthenware objects made in Korea from the first century through contemporary times. Titled ŌĆ£Perfectly Imperfect: Korean Buncheong Ceramics,ŌĆØ the showŌĆö co-organized with the National Museum of Korea (NMK)ŌĆö runs until December 7th, 2025.

The exhibit is the first fruit of a $900,000-plus art grant from the NMK to the DAM that will fund a series of Korean art exhibitions and programs over three years.

As its title indicates, the ceramics show spotlights sublime buncheong works, most from the 15th century. The exhibitŌĆÖs two primary curators ŌĆö Hyonjeong Kim Han, the DAMŌĆÖs Joseph de Heer Curator of Arts of Asia, and Ji Young Park, the DAMŌĆÖs National Museum of Korea Fellow of Korean Art ŌĆö are women, but Korean ceramists are almost exclusively men. In galleries aglow with the gray-green pottery, the curators spoke to the importance of buncheong ware for Korean identity and history, as well as the progression of ceramics once freed from imperial mandates.