Since the late 19th-century, Egypt has continued to offer up astounding archaeological treasures that have found their way into museums around the globe, becoming tourist attractions helping to support local economies. Worldwide interest in Egyptology shows no signs of slowing down. Much of the ancient wonders that have so far been unearthed have necessarily remained in storage or languished in outdated museums. That is about to change.

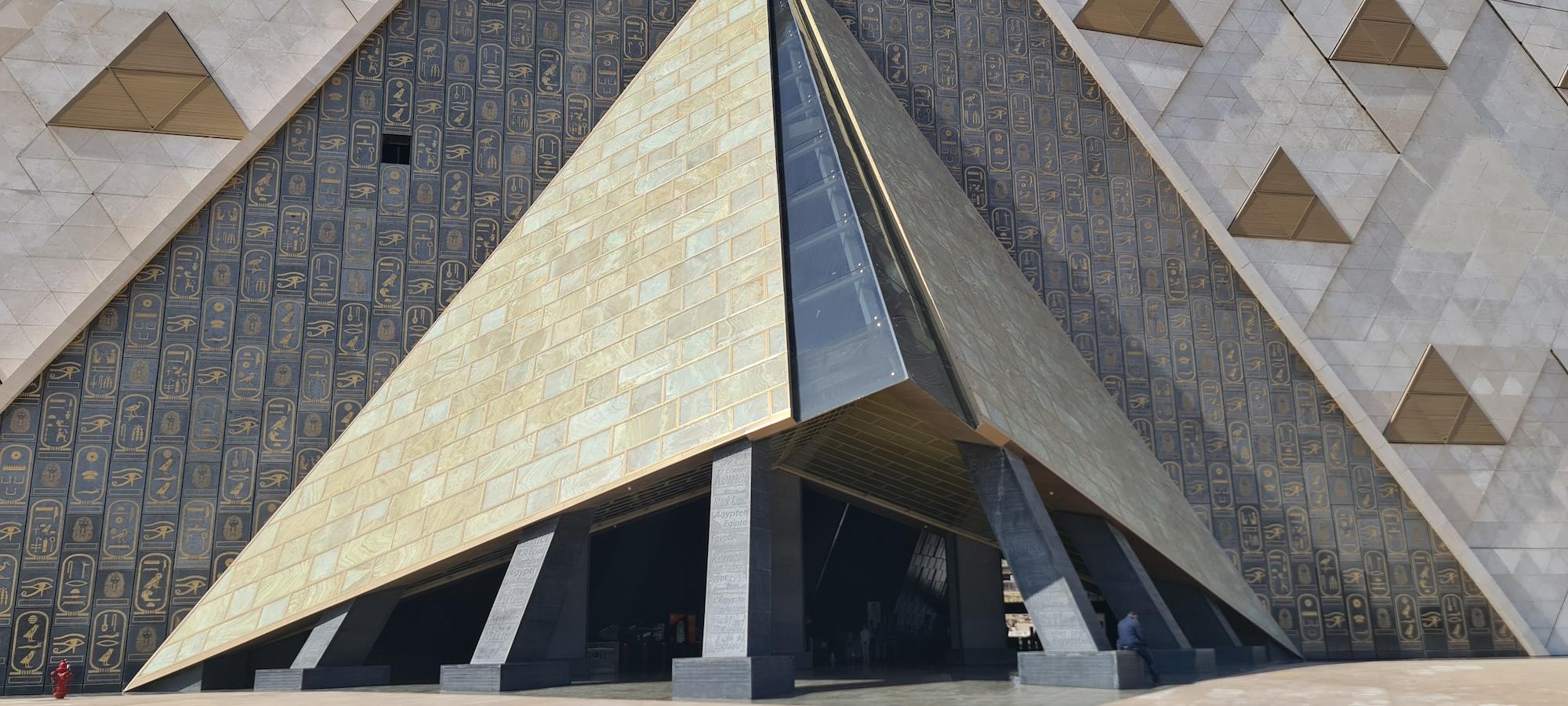

The long awaited, aptly titled Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) is finally opening to the public in stages, with the complete launch scheduled for July 3, 2025. Located a little over a mile away from the site of the Giza pyramids, the GEM is the largest museum in the world dedicated to a single culture. Their website describes the ŌĆ£twelve meticulously curated exhibition halls of the Main Galleries to explore EgyptŌĆÖs rich history, spanning from prehistoric times to the Roman era,ŌĆØ some part of which will trace the significant impact of HatshepsutŌĆÖs reign.