The Tate, a network of four museums dedicated to the legacy of British art, holds a large selection of Colquhounâs work in their permanent collection, much of which has never been publicly shown before. The Tateâs acquisition in 2019 of her entire archive has sparked a thorough re-evaluation of her legacy. The curators were able to draw on that material to feature over 200 works along with theater projects, ephemera, letters, notes and sketches tracing the artistâs exploration of the occult, myth, and magic with a particular focus on how these elements relate to divine feminine power. Considered one of the most radical artists of her generation, Colquhounâs originality, along with her exploration of taboo subject matter often related to gender and sexuality, seems prescient.

Born in 1906 in Shillong, British India and the daughter of a British diplomat, Colquhoun was academically precocious, demonstrating an interest in spirituality and the occult as a teenager. She had some formal art training, having attended the Slade School of Art in London, and in 1929, she received the Slade's Summer Composition Prize for her painting Judith Showing the Head of Holofernes.

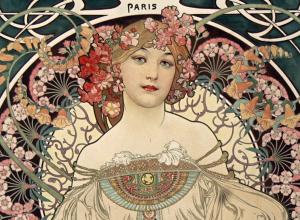

Although many of the most well-known paintings of Judith and Holofernes were done by men, that subject has served as a feminist tour de force for several talented, bold artists like Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656), as well as Colquhoun. Even in this early work, one of the largest in the exhibition, Colquhounâs distinctive palette, modeling, and distortion of bodily form was evident.